Mastering Endodontics: A Holistic, Detail-Rich Playbook for Patient-Centered Care

- Sep 1, 2025

- 6 min read

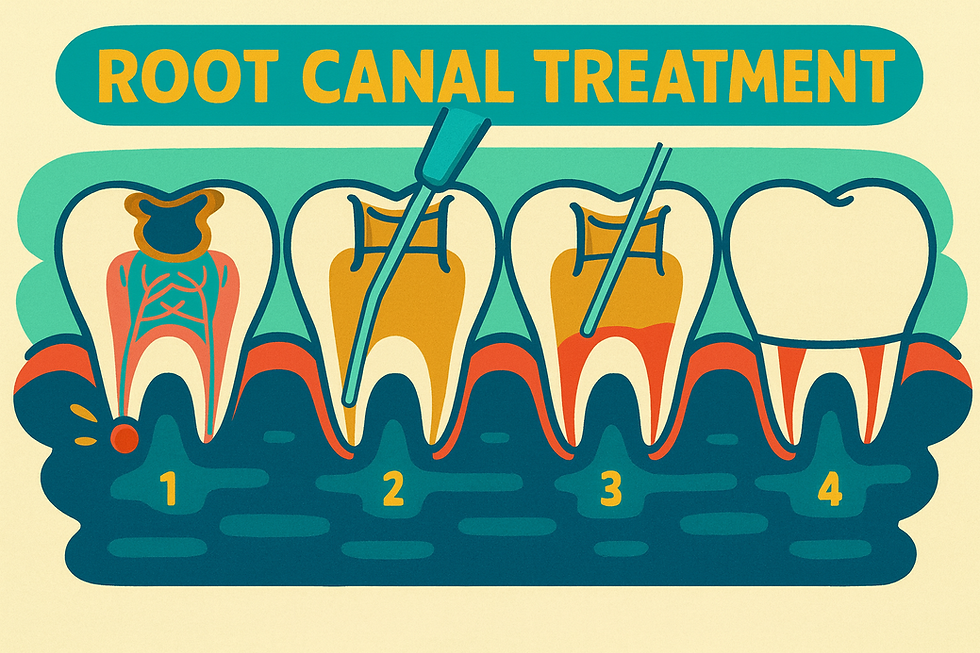

Endodontics sits where precision, anatomy, and empathy meet. Tools evolve, files get shinier, and protocols get tweaked—but the bedrock of excellent care is unchanged: meticulous diagnosis, profound anesthesia, disciplined cleaning and shaping, judicious irrigation, airtight obturation, and clear communication (including when to refer). Below is a comprehensive, keep-nothing-back guide you can put straight into practice.

1) The Cornerstone: Diagnosis & Anatomy

Diagnosis is about the “why,” not just the “what.” Before you even meet the patient:

Radiographs: Always take two periapicals at different angles plus a bitewing to rule out referred pain and expose hidden anatomy.

Chief complaint & pain history: Ask onset, triggers (hot/cold/bite), intensity, “Does it wake you at night?”

Systematic diagnostic protocol:

Probing for periodontal communication, fractures.

Percussion (contralateral side first → then affected).

Bite stick (tooth sleuth) for cracked cusp pain.

Palpation for swelling/sinus tracts (trace with GP if present).

Cold test: Cotton pellet on locking pliers with Endo Ice — most sensitive pulp vitality test.

Occlusion check, especially protrusive: Hyperocclusion can mimic or worsen endodontic pain.

Pulpal & periapical classifications:

Pulp: normal, reversible pulpitis, symptomatic/asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis, necrotic, previously initiated, previously treated.

Periapical: normal periodontium, symptomatic/asymptomatic apical periodontitis, acute/chronic apical abscess.

If inconclusive → wait for localization or refer. Starting on the wrong tooth is a cardinal error.

2) Root Canal Anatomy: Two Cardinal Rules

Find all canals.

Reach the end of every canal.

A millimeter is a mile in endodontics. Missed canals or short instrumentation are the most common causes of failure.

Premolars: The Epitome of Variability

Premolars are considered highly variable teeth, and understanding their canal patterns is essential.

Maxillary First Premolar

1 canal: ~9%

2 canals: ~85%

3 canals: ~6% → rule of thumb: always look for one more canal than expected.

Access: Oval, centered in occlusal table, wider buccolingually.

Maxillary Second Premolar

1 canal: ~48%

2 canals: ~51%

3 canals: ~1%

Joining patterns:

~75% join into one canal at the apex.

~24% remain separate.

~1% remain three canals.

Access: Oval, similar to first premolar.

Mandibular First Premolar

1 canal: ~70%

2 canals: ~29.5%

3 canals: ~0.5% (more common in certain ethnic groups).

Access: Oval, sometimes slightly lingual.

Challenges: Can be difficult even under magnification. CBCT often necessary.

Second canal (if present): Usually tucked in the lingual wall, starting almost at a right angle. Requires careful adjustment to achieve straight-line access and avoid file separation.

Mandibular Second Premolar

1 canal: ~97.5%

2 canals: ~2.5%

Access: Oval, sometimes shifted slightly lingual.

Other Key Anatomical Highlights

Maxillary central incisor: One canal, many laterals; perforation risk buccally.

Maxillary lateral incisor: Frequent dilacerations; possible dens invaginatus.

Maxillary canine: Very long; keep 31 mm files.

Maxillary first molar: MB2 present ~96%. Trough ~2 mm lingual/apical to MB1; CBCT recommended.

Mandibular incisors: Two canals ~41%; perforation risk high.

Mandibular first molar: Four canals ~29%; middle mesial canal 2–18%.

Supernumerary roots:

Radix Entomolaris: Distolingual extra root.

Radix Paramolaris: Mesiobuccal extra root.

Both are more common in Asian populations, usually with one narrow, angled canal and higher risk of file separation.

Mandibular second molar: MB2 sometimes elusive; C-shaped anatomy in ~8% (up to 15% in Asian populations).

Laws of access preparation (centrality, concentricity, CEJ, color change, symmetry) ensure safe, conservative entry. Remember: pulp chamber floors are darker; reparative dentin is lighter and can hide orifices.

3) Anesthesia: The Patient’s Ultimate Judge

Profound anesthesia is the benchmark of comfort.

Protocols:

Maxillary teeth: ~2 carpules articaine → 1.5 buccal + 0.5 palatal.

Mandibular teeth: 2 carpules lidocaine (IAN block) + 0.5–1 articaine buccal/lingual infiltration.

Slow injection (≥1 min): deeper and more comfortable anesthesia.

Hot teeth strategies:

PDL injection: Ligajet, ultrashort needle, six line angles with back pressure. Immediate onset, ~20 min duration.

Intrapulpal injection: Painful seconds, then profound ~15–20 min anesthesia.

Why anesthesia fails: inflamed tissue reduces efficacy, block missed, nerve potentials altered, rare TTXR resistance, or anxious patients (consider sedation).

Always confirm with cold test; a negative result means 80% less risk of intra-op pain.

4) Instrumentation, Irrigation & Obturation

Concepts matter more than brands.

Instrumentation

Open coronally first → easier apical negotiation.

Back-and-forth method: alternate coronal shapers, hand files, and path files (e.g., ProGlider).

Hybrid finishing: after S1 → ProTaper S/F → then .04 taper for apical enlargement with less coronal removal.

Patency & recapitulation: Keep a small file passing WL (0.5–1 mm beyond) throughout to prevent blockage.

Modern endodontics is shaped by the choice of instrumentation system. While both rotary and reciprocating systems can shape canals effectively, understanding their differences helps clinicians choose the safest and most efficient option for each case.

Rotary Instrumentation

Motion: Continuous 360° rotation.

Advantages:

Produces smooth, tapered preparations.

Excellent for controlled shaping in straighter canals.

Compatible with a wide range of file designs and tapers.

Better tactile feedback during shaping.

Limitations:

Higher risk of torsional fracture in narrow or calcified canals due to continuous rotation.

Requires careful glide path preparation before use.

Popular rotary systems:

ProTaper Gold (Dentsply Sirona): Excellent flexibility, efficient cutting, widely adopted.

Vortex Blue (Dentsply Sirona): Heat-treated NiTi for added resistance to cyclic fatigue.

K3XF (SybronEndo): Smooth transition design, flexible yet durable.

Reciprocating Instrumentation

Motion: Alternating back-and-forth movement (e.g., 150° CCW cutting, 30° CW disengage).

Advantages:

Reduced file stress — reciprocation minimizes torsional load, lowering risk of separation.

Simplified protocols — many systems use a single file for the majority of shaping.

Easier learning curve for general dentists; fewer instruments needed.

Particularly useful in calcified, curved, or retreatment cases.

Limitations:

Preps may be slightly less smooth compared to rotary, sometimes needing finishing.

Some clinicians feel tactile feedback is reduced compared to rotary systems.

Popular reciprocating systems:

WaveOne Gold (Dentsply Sirona): Single-file system, heat-treated alloy, excellent for most cases.

Reciproc Blue (VDW): Strong, flexible, and efficient in difficult or curved canals.

X1 Blue Reciproc (FKG): Single-file simplicity, designed for minimally invasive shaping.

Clinical Pearl

For beginners or those handling a high volume of cases, reciprocating systems like WaveOne Gold or Reciproc Blueoffer simplicity, safety, and efficiency — reducing stress and the likelihood of file separation. For advanced users, rotary systems like ProTaper Gold or Vortex Blue provide precision and versatility, especially when paired with careful glide path management and irrigant activation.

Irrigation

Mechanical shaping cleans only ~35% of walls; irrigants do the rest.

Solutions:

NaOCl 6% (tissue dissolution).

EDTA 17% (smear layer removal, tubule opening).

CHX 2% (retreatments).

Rules: Never mix NaOCl + CHX directly → brown precipitate; always flush with EDTA in between.

Delivery: 30g side-vented needles, 1–2 mm short WL.

Activation: Ultrasonic activation enhances efficacy.

Obturation

Warm vertical condensation with cone showing good tug-back at WL.

Use a smaller taper cone than final rotary to avoid extrusion.

Place an orifice barrier (composite) before temporary for coronal seal.

5) One Visit vs Two Visits

Emergencies: often 2 visits (pulpectomy first).

Retreatments: ~98% are 2 visits (more infected).

Symptomatic, swollen, or draining: 2 visits preferred.

Large PARLs or complex anatomy: 2+ visits.

Straightforward cases: 85–90% can be completed in 1 visit — but set patient expectations that 2 may be necessary.

6) Retreatment, Gutta-Percha Removal & Apicoectomy

Retreatment is first choice when the root length is suspect.

Gutta-Percha Removal Protocol

Use 25/.06 ProFile (or .04).

Create 2 mm well, apply chloroform, let soak, rotate at 1000 RPM to 1 mm short WL.

Alternate solvent and file; finish with smaller hand files apically.

Flush solvent thoroughly before re-obturation.

Why 25/.06 vs 25/.04 matters:

Both are #25 at D0 (0.25 mm tip).

.06 taper: Becomes thicker faster → more stiffness, stronger lateral engagement → “screws in” and grabs GP, pulling it coronally. Best for straight, large canals.

.04 taper: Slimmer, more flexible → less grip but safer in curved/tight canals (lower fracture risk).

Apicoectomy

Useful when separated files or calcifications prevent patency.

Resection of last 3 mm exposes and disinfects apical isthmuses.

Limits: Only treats apical ~6 mm; won’t address coronal leakage.

Contraindications: proximity to sinus, mental nerve, heavy buccal bone.

Sometimes monitoring is best (e.g., asymptomatic post-core teeth).

7) Pain Management & Post-Operative Care

Pre-op: Ibuprofen 600 mg (or acetaminophen 650 mg).

Post-op: Ibuprofen 600 mg q6h × 3 days. Add acetaminophen as needed.

Escalation: narcotic add-on for severe pain; steroids (Medrol pack) for swelling.

Antibiotics: only for necrotic/swollen/abscess teeth. Amoxicillin first-line; clinda or Augmentin alternatives. Always pair with probiotics.

Set patient expectations:

Soreness for 3–5 days, should improve daily.

More pre-op percussion pain = more post-op pain.

Lower molar retreatments with PARLs have higher flare-up risk.

Swelling occurs in ~10% with PARLs; may require antibiotics/steroids.

Crown within 1–2 weeks; Cavit <1 month.

Next-day post-op call builds trust.

8) The Art of Referral

Refer when: retreatments, large PARLs, symptomatic/swollen cases, anesthesia failures, calcified/long canals, complex anatomy, or if difficulty exceeds your comfort.

Best practices:

Explain why referral is needed.

Prepare patients for new radiographs/CBCT and re-evaluation.

Provide a complete referral slip (diagnosis, recent work, reason).

Train front office with triage scales (P1–P3) for urgency.

Never promise same-day definitive treatment at specialist offices.

Closing Thought

Great endodontics is disciplined kindness: rigorous diagnostics, respect for anatomy down to fractions of a millimeter, and patient-first decisions—including the humility to refer. When we honor the biology and the human experience—through profound anesthesia, thoughtful shaping and irrigation, airtight obturation, clear expectations, and seamless specialist collaboration—we turn millimeters into miles of comfort and success for our patients.

Dr. Noor N. Ay Toghlo BSc DMD

Comments